Land-trust missions conform to United Nations “Agenda 21”

By Diana George Chapin

Maine’s vast northern and downeast forestland is viewed by some as the last wilderness frontier in the country. With large areas preserved in perpetuity by state and federal possession, an increasing amount of acreage is being conserved through easements and controlled by private non-profit, board-of-directors-governed corporate land trusts.

In an announcement in May of this year, The Nature Conservancy (TNC), the Forest Society of Maine (FSM) and Plum Creek unveiled the acquisition of one of the largest conservation easements in U.S. history. A press release from The Nature Conservancy at the time of the announcement stated: “The 363,000-acre easement, which will be held by the Forest Society of Maine, will permit recreation, including hunting, fishing, hiking and snowmobiling on set trails; as well as forestry that meets the standards of the Sustainable Forestry Initiative (SFI) and other conservation guidelines.”

The sizable easement connects over 2 million acres of conservation-easement-controlled land and includes some land donated by Plum Creek. Additional acreage covered by the conservation easement was purchased by The Nature Conservancy, using funds raised as part of its ongoing $100 million “Sustainable Maine, Sustainable Planet” campaign, as well as some funds raised by the Forest Society of Maine.

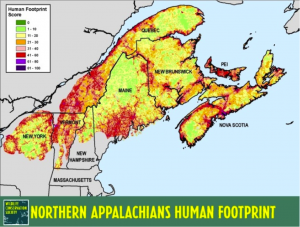

From his office in Bangor, Alan Hutchinson serves as executive director of FMS. On a cool day in spring, before the public announcement TNC made from Portland, he pulled out a series of maps called the “Human Footprint Project.” He displayed them across a table in his office, explaining that the red areas of the map indicated the greatest human activity; the pink areas denoted lesser interactions; the yellow for minimal activity; and the green for virtually undisturbed areas.

Using data gathered from eastern Canadian provinces and northeastern states, Hutchinson said the maps were crafted with information on types of roads, road density and permeability of the road surface, housing density and types of housing. Map developers examined the amounts and locations of land in agricultural production, as well as measures of how intense the conversion of native, natural lands has been to agricultural production.

Map source: http://programs.wcs.org/canada/MapGallery/tabid/2560/Default.aspx

“They melded it all together, state to state and province to province, and they made this map,” said Hutchinson, pointing to the document that effectively describes activities independent of international boundaries. “We fell in love with it.”

“It’s a wonderful piece of work that was done a few years ago,” he said. “Some of the work was done by some people at the University of Maine and with a consortium of environmental conservation groups that were looking at particularly the northeast—the northern Appalachia eco-region, trying to get a handle on where the large blocks of unbroken forestlands still are that haven’t had much an impact yet from human development.”

The maps can help environmentalists, land and animal habitat preservationists and conservationists define areas for acquisition.

“They’re trying to figure out where could you expect to maybe maintain things like viable populations of Canada lynx or wolves—the large northern forest predators—for example, pine martin, things of that sort. Where are these blocks, and are there ways they can be still connected to some of these big blocks to maintain travel corridors and critical mass of those sites,” he said.

Hutchinson said he would like the map to look the same 100 years from now. “At this stage it’s just data; there’s no agenda assigned to it,” he said.

But Dr. Michael Coffman begs to differ.

For decades Coffman, through his work with Environmental Perspectives in Bangor, has sought to educate people across the globe about the United Nations’ “Agenda 21.” The UN describes the Agenda as “a comprehensive plan of action to be taken globally, nationally and locally by organizations of the United Nations System, governments and major groups in every area in which human impacts on the environment.”

Coffman recently published a new book, entitled “Plundered: How Progressive Ideology is Destroying America,” in which he describes how Agenda 21 and other geopolitical goals are destroying property rights and free market enterprise in America.

“Most Americans have never heard of Agenda 21, even though there are over 3 million pages about Agenda 21 on the web,” Coffman said. “Yet most planners and environmentalists are keenly aware of it. They will claim they are not implementing Agenda 21, however. They are technically correct. They are technically implementing ‘Sustainable America’.”

“The United Nations Agenda 21 is a 40-chapter document signed by President Bush in 1992 during the Earth Summit at Rio de Janeiro,” Coffman said. “Ostensibly a plan to reorganize man’s activities to live in harmony with nature, in reality it is a radical plan to reorganize man around the central organizing principle of nature. It impacts every aspect of human activity.

“In 1993 President Clinton convened the President’s Council on Sustainable Development to fulfill the U.S.’s commitment to Agenda 21,” Coffman said. “In 1996 that goal was fulfilled with the publication of ‘Sustainable America’, a radical plan to control all development and use of natural resources. Seven sub-documents of Sustainable America were published that redirect the mission statements of every federal agency. Every federal grant was linked to Sustainable America. The mission for federal agencies shifted from helping the American people to protecting the environment from the American people.”

Coffman reports that transportation dollars were shifted from building highways to building extremely expensive alternative mass transportation, like light rail and high-speed rail. The same was true of shifting from fossil fuels to extremely expensive alternative fuels. Rigid and very expensive comprehensive planning called “Smart Growth” became the “in” thing for cities and communities to do because huge federal grants were available.

“A key component of protecting biodiversity was to set huge areas of land aside for nature,” Coffman said. “These are essentially de facto wilderness areas interconnected with wilderness corridors. The United Nations Global Biodiversity Assessment, the heart of Agenda 21 to protect biodiversity, calls for nearly a half of the nation to be put into these reserves and corridors. The federal government cooperated with states to implement the GAP program that uses geographic information layering to define where ecological sensitive areas needed protection.”

Coffman says whether or not they know it, land trusts play a key role in implementing Agenda 21.

“Realizing that the government could never buy enough land to cover up to 50 percent of the landscaped allegedly needed to protect biodiversity, the Environmental Grantmakers Association (made up of about 140 major U.S. foundations in 1992—over 200 today) created a huge program in 1992 to create and fund land trusts to buy conservation easements that eliminate any development and begin to impose land-use restrictions,” he explains. “Maine became the state with the largest conservation easement in the U.S. when Pingree Associates put 760,000 acres under an easement with 45 land trusts led by the New England Forestry Foundation in 2001. Both the State of Maine and the federal government contributed $5 million for the easement.”

While FSM and environmental groups claim conservation and economy building can go hand in hand, the language they use to describe directing human settlements along existing transportation corridors is the language of “Smart Growth,” “Sustainable Development” and, in turn, Agenda 21.

“You can see the road network,” Hutchinson said, pointing to the Human Footprint Project map. “Our hope is that growth will occur primarily along these threads where you already have development. Over time, through various mechanisms and means, these big blocks and areas connecting these big blocks can stay undeveloped while growth occurs elsewhere, and communities can prosper from both growth along these threads, but then prosper from having some credible natural resource base.”

By “mechanisms and means,” Hutchinson is referring to encumbering land held by private landowners with conservation easements that ensure no development in perpetuity.

“As a land trust, the one that we are ready to deliver—and are good at—is conservation easements,” Hutchinson said. “When a landowner is bumping into some kind of a struggle, I think easements have proven that they can provide an incredibly valuable piece of the puzzle.”

Coffman couldn’t disagree more.

“Recent global research has clearly shown that wealth cannot be created without private property rights,” he said. “Conservation easements gut property rights, and the systematic tightening of environmental regulations may take what is left. Land withdrawal creates scarcity, which always increases cost.

“While we need to practice conservation, the preservation mentality behind Agenda 21 strips property owners of the range of land management practices needed to prosper and protect the environment,” Coffman said.

In an event open to the public, Rosa Koire, author of “Behind the Green Mask: UN Agenda 21,” will be speaking) on Monday, August 13 from 6:30 to 8:30 pm. in Waldoboro at the First Baptist Church at 7 Grace Avenue (just north of Moody’s Dinner on Route 1).

Diana George Chapin is a freelance writer and a fourth-generation family farmer from Montville, Maine.

This is part of an ongoing series about Maine Land Trusts – Read all articles here.

http://www.themainewire.com/2012/08/land-trust-missions-conform-united-nations-%E2%80%9Cagenda-21%E2%80%9D/

![[Most Recent Quotes from www.kitco.com]](http://www.kitconet.com/images/sp_en_8.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment